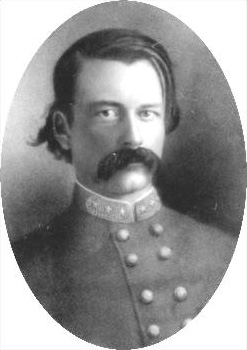

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN ADAMS, CSA

by member Evelyn Risk My great great uncle, Brigadier General John Adams was the brother of my great grandfather, Major Thomas Patton Adams, my direct UDC ancestor. Brigadier-General John Adams, was born at Nashville, Tennessee, July 1, 1825. His father and mother came to Tennessee from County Tyrone, Ireland, and afterward located at Pulaski, and it was from that place that young Adams entered West Point as a cadet, where he was graduated in June, 1846. On his graduation he was commissioned second lieutenant of the First Dragoons, then serving under Gen. Philip Kearny. At Santa Cruz de Rosales, Mexico, March 16, 1848, he was brevetted first lieutenant for gallantry, and on October 9, 1851, he was commissioned first lieutenant. In 1853 he acted as aide to the governor of Minnesota with the rank of lieutenant-colonel of State forces, this position, however, not affecting his rank in the regular service. It was in Minnesota that he met and married Georgia McDougal, the daughter of a distinguished army surgeon. He was promoted in his regiment to the rank of captain, November, 1856. On May 27, 1861, on the secession of his State, he resigned his commission in the United States army and tendered his services to the Southern Confederacy. He was first made captain of cavalry and placed in command of the post at Memphis, whence he was ordered to western Kentucky and thence to Jackson, Miss. In 1862 he was commissioned colonel, and on December 29th was promoted to brigadier-general. On the death of Brig.-Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, May 16, 1863, Adams was placed by General Joseph E. Johnston in command of that officer's brigade, comprising the Sixth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Twentieth, Twenty-third and Forty-third Mississippi regiments of infantry. Receiving commendation for his brave service, Adams continued with General John Bell Hood during the Franklin and Nashville Campaigns, and served briefly under Major General Nathan B. Forrest. He was in Gen. J. E. Johnston's campaign for the relief of the siege of Vicksburg, in the fighting around Jackson, Miss., and afterward served under Polk in that State and marched with that general from Meridian, Miss., to Demopolis, Ala., thence to Rome, Ga., and forward to Resaca, where he joined the army of Tennessee. He served with distinction in the various battles of the campaign from Dalton to Atlanta, he and his gallant brigade winning fresh laurels in the fierce battles around the "Gate City." After the fall of Atlanta, when Hood set out from Palmetto for his march into north Georgia in the gallant effort to force Sherman to return northward, Adams' brigade was much of the time in advance, doing splendid service, and at Dalton capturing many prisoners. It was the fate of General Adams, as it was of his friend and classmate at West Point, Gen. Geo. E. Pickett, to reach the height of his fame leading his men in a brilliant and desperate, but unsuccessful, charge. But he did not come off so well as Pickett; for in the terrific assault at Franklin, Adams lost his life. Adams was killed in the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864, while leading his regiment in a forceful but unsuccessful attack on Union forces. In the midst of the deadliest fighting around the cotton gin, witnesses recall seeing the conspicuous Adams astride his white steed, Old Charley. Well out in front of his brigade, he dashed towards the Federal lines, seemingly impervious to the hail of bullets. Spurring his mount to jump the parapets, the horse came crashing squarely down on top of them, dead. Adams fell from the horse and into the ditches, his body riddled with nine bullets. Breathing his last, Adams was heard to say; "It is the fate of a soldier to die for his country." Lieut.-Col. Edward Adams Baker, of the Sixty-fifth Indiana infantry, who witnessed the death of General Adams at Franklin, obtained the address of Mrs. Adams many years after the war and wrote to her from Webb City, Mo. This letter appeared in the Confederate Veteran of June, 1897, an excellent magazine of information on Confederate affairs, and is here quoted: "General Adams rode up to our works and, cheering his men, made an attempt to leap his horse over them. The horse fell upon the top of the embankment and the general was caught under him, pierced with bullets. As soon as the charge was repulsed, our men sprang over the works and lifted the horse, while others dragged the general from under him. He was perfectly conscious and knew his fate. He asked for water, as all dying men do in battle as the life-blood drips from the body. One of my men gave him a canteen of water, while another brought an armful of cotton from an old gin near by and made him a pillow. The general gallantly thanked them, and in answer to our expressions of sorrow at his sad fate, he said, 'It is the fate of a soldier to die for his country,' and expired." General A. P. Stewart on General John Adams at Franklin: “At Franklin there was not a more natural or sublimer display of true heroism than was made by Brigadier-General John Adams, a Tennessean, commanding a brigade in Loring’s division, Stewart’s corps. It was natural because it emanated spontaneously from one whose very nature was heroic and who, consequently, could not act otherwise than heroically.” (Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee by Bromfield Lewis Ridley (Member of Stewart’s staff), 1906. In the battle lines, blue and gray, all eyes turned to Adams. Leaping “Old Charley” to the top of the works (6 feet high by most accounts, including headlogs) Adams yelled for his men to follow and take the entrenchments. Stunned by Adams’ bravery and audacity, some Union soldiers shouted, “Do not kill him! Do not shoot that man!” And in this still moment amidst the hurricane of bullets and shrieks Adams on his horse between the fighting lines he must have know he could not live. This was the supreme moment, from his Nashville upbringing and Pulaski early life to West Point, Mexican War battles and Minnesota frontier fighting, it had all come to this moment – on top of his horse, on top of the Union works in the midst of a savage battle so near his home. He could not live, it was clear. But there were the shouts – “Do not kill him!” They would capture him, and he would be sent to Johnson’s Island, or Elmira, or even Fort Warren- a prisoner in the dark. Perhaps he thought that it just wasn’t right, it was no way to end. His men needed his leadership and example. They needed it now. From his horseback high above the Federals in the works, he lunged for the national flag carried by the 65th Indiana Volunteers. Grabbing the flag pole horse and rider are fired on by the color guard. He is shot 9 times and falls to the top of the Union works, his black warhorse falls dead on top of him, pinning him to the Union entrenchment. A soldier named Stevens, of the 65th Illinois fighting on the Union line just to the left of their Indiana comrades and the right of the Carter House wrote of the scene: “Our Colonel Stewart … called to our men not to fire on him, but it was too late. Gen. Adams rode his horse over the ditch to the top of the parapet, undertook to grasp the ‘old flag’ from the hands of our color sergeant, when he fell, horse and all, shot by the color guard.” (Eyewitnesses at the Battle of Franklin, Logsdon, Kettle Mills Press, 2000) Colonel Tillman Stevens of the 65th Indiana, in a letter to the Confederate Veteran magazine (1903) described what he saw: “We looked to see him fall every minute, but luck seemed to be with him. We were struck with admiration… He was too brave to be killed. The world had but few such men. … We saw scores of officers fall from their mounts… but the one great spirit who appealed the strongest to our admiration was Gen. John Adams… He was riding forward through such a rain of bullets that no one had any reason to believe he would escape them all, but he seemed to be in the hands of the Unseen, but at last the spell was broken and the spirit went out of one of the bravest men who ever led a line of battle.” (The Gallant Dead: Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War, by Derek Smith, Stackpole, 2005.) As they continue to defend their position against repeated charges by the Confederates, Union soldiers take the mortally wounded general from under his dead horse, Old Charley’s forelocks hanging over the Union side and hind legs over the other. Adams cannot live long. The Indiana and Illinois soldiers take him back behind their lines a short way, and lay him down. Made as comfortable as possible, he requested that he be sent back to the Confederate lines. But this was a luxury the Federal soldiers couldn’t afford to give as the ongoing Southern attacks against their line made any such transfer impossible in the extreme. “As soon as the charge was repulsed our men sprang upon the works and lifted the horse, while others dragged the General from under him. He was perfectly conscious, and knew his fate. He asked for water, as all dying men do in battle, as the life blood drips from the body. One of my men gave him a canteen of water, while another brought an arm load of cotton from an old gin near by and made him a pillow. The General gallantly thanked them, and, in answer to our expressions of sorrow at his sad fate, he said: ‘It is the fate of a soldier to die for his country,’ and expired.” Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Adams Baker, 65th Indiana infantry – (Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee by Bromfield Lewis Ridley (Member of Stewart’s staff), 1906.) Adams would lay dead behind the Union lines as his men charged again and again on the line, killing and dying. Hundreds would be killed here in this sector of the battle, often fighting hand to hand. But the ill-fated advance, and the desperate bloody charges would have no effect but the killing. The Union army would withdraw from their lines around 11.30, and march for Nashville in the chill darkness of the first day of December. 1864 was coming to a close and the Confederacy was further from victory than they had been only hours before. The mighty Army of Tennessee had broken itself on the earthworks south of Franklin. Once again the Union army would escape Hood just as it had the previous day at Spring Hill. Adams’ body was recovered at the same time that Patrick Cleburne was found, some fifty yards away just in front of the Cotton Gin with one bullet hole in his chest. Placed in the same ambulance they were laid on the porch of Carnton, passing over the same ground that Adams had charged across on Old Charley just hours before. What a scene, the Confederate Generals Patrick Cleburne, Otho Strahl, John Adams, and Hiram Granbury laid out in a line on the back porch of Carnton, where hundreds of their comrades were fighting for their lives in this beautiful ante-bellum mansion, now a hospital its floors covered in blood and the amputated limbs of the wounded in piles thrown outside the first floor windows now operating theaters. In 1896, Lt. Col Baker of the 65th Indiana wrote a letter to John Adams widow inquiring as to his character and providing her with his recollection of the general’s death at Franklin. The colonel wrote of the General’s bravery and the disposition of his personal effects including his saddle which had been given to General Casement, now living in Painesville, Ohio. Baker concluded his letter by inviting Mrs. Adams’ sons to visit him and informing her that he would communicate to General Casement regarding the saddle if she requested it. Baker’s letter is extraordinary. Casement’s continues the theme. It is of moment, and I include it here in it’s entirety, as follows: Painesville, Ohio., November 23, 1891. Mrs. Georgia McD. Adams. Dear Madam: Major Baker, of Webb City, Mo., informs me that you have expressed a desire to obtain the saddle used by General Adams at Franklin, Tennessee, in his last and fatal ride on the unhappy day that caused so many hearts to bleed on both sides of the line. It was my fortune to stand in our line within a foot of where the General succeeded in getting his horse’s forelegs over the line. The poor beast died there, and was in that position when we returned over the same field more than a month after the battle. The saddle was taken off the horse and presented to me before the charge was fairly repulsed; that is why I have kept it all these years. It is the only trophy I have of the great war, and I am only too happy to return it to you. It has never been used since the General used it. It has hung in our attic. The stirrups were of wood, and I fear that my boys in their pony days must have taken them, for I cannot find them. I am very sorry for it. General Adams fell from his horse from the position in which the horse died, just over the line of the works, which were part breast-works and part ditch. As soon as the charge was repulsed I had him brought on our side of the works, and did what we could to make him comfortable. He was perfectly calm and uncomplaining. He begged me to send him to the Confederate line, assuring me that the men that would take him there would return safe. I told him that we were going to fall back as soon as we could do it safely, and that he would soon be in possession of his friends. It was a busy time with me. Our line was broken from near its center up to where I stood in it, and in restoring it and repulsing other charges I was too busy to again see the General until after his gallant life had passed away. I had his ring and watch taken care of; his pistol I gave to one of the Colonels of my brigade, and do not know what became of it. These are briefly the facts connected with the death of General Adams. The ring and watch were sent to you through a flag of truce and a receipt taken for them. The saddle will be expressed to you tomorrow. Would that I had the power to return the gallant rider! There was not a man in my command that witnessed the gallant ride that did not express his admiration of the rider and wish that he might have lived long to wear the honors that he so gallantly won. Wishing you and his children much happiness, I am yours truly, J. S. Casement Federal casualties were light compared to the Confederate losses. In just five hours of heavy fighting, the Confederate casualties numbered over 7,000, including wounded, captured and killed. The Federals lost only 2,500 men. 13 Confederate generals were also lost, as well as 65 regimental commanders. For all practical purposes, the Army of Tennessee died at Franklin. Major Thomas Patton Adams (my direct UDC ancestor) was with his brother General John Adams during most of his service, serving on his staff, and after the Battle of Franklin, continued with Hood’s Army of Tennessee until its dissolution and surrender in Bentonville, NC, April 26, 1865. “It is the blackest page in the history of the war of the lost cause. It was the bloodiest battle of modern times in any war. It was the finishing stroke to the independence of the southern Confederacy. I was there. I saw it. My flesh trembles, and creeps, and crawls when I think of it today.” Private Sam Watkins, 1st Tennessee Regiment, Columbia, Tennessee. Army of Tennessee, commanded by General John Bell Hood Stewart’s Corps, commanded by Lt. General Alexander P. Stewart Loring’s Division, commanded by Major General William W. Loring Adam’s Brigade, commanded by Brig. General John Adams, with Colonel Robert Lowry Units Which Served under Gen. Adams: Sixth Mississippi Infantry Regiment Fourteenth Mississippi Infantry Regiment Fifteenth Mississippi Infantry Regiment Twentieth Mississippi Infantry Regiment Twenty-third Mississippi Infantry Regiment Forty-third Mississippi Infantry Regiment |